|

There is no better feeling than taking to a paper, project, or other writing assignment with gusto – having a great idea on the brain and finding yourself ready to articulate it onto the page. However, as every writer (and college student) may know, this utopia is not always the reality. Sometimes, you hit a wall. This wall, this “writer’s block,” can seem insurmountable and can tempt us to throw in the towel and call it quits. We’re here to say – hold on to that towel! Believe it or not, there are a few crafty methods we can employ in order to beat this block. Here are some of the ideas HUB writing partners suggest:  Discuss your writing with others:

Or, discuss with HUB writing partners:

Or, discuss with yourself!

Take a break:

Visual representations / flowcharts:

Brainstorming / creating an outline:

Freewriting:

Revising / Reading:

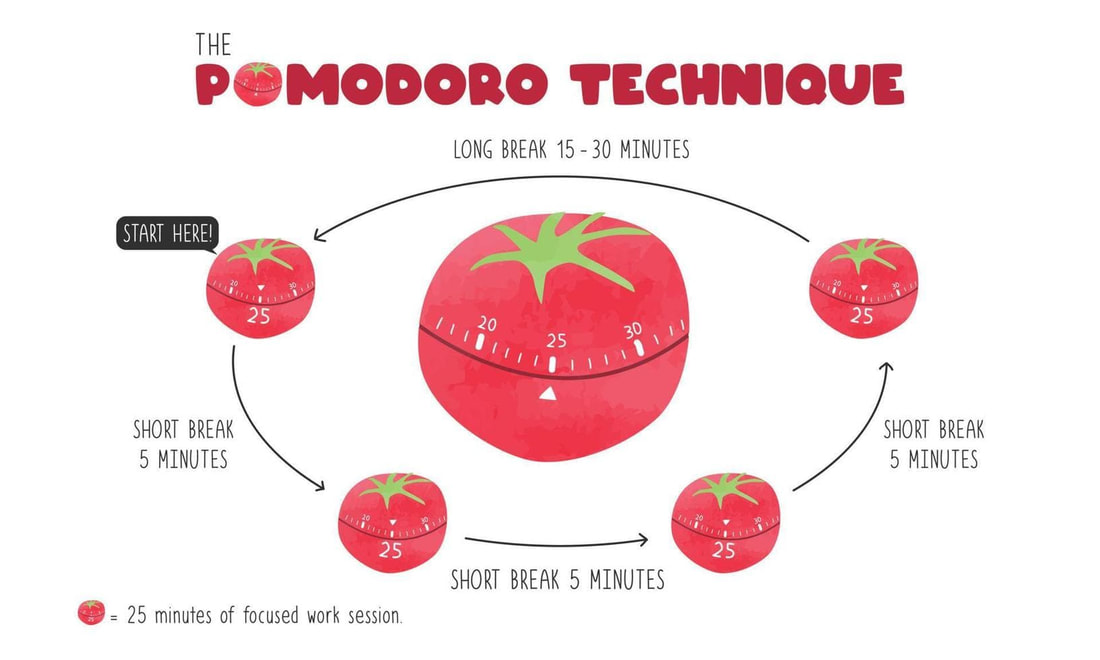

Pomodoro Method:

Some other advice:

About the Author

Maha Issa has been a graduate writing partner at the HUB writing center since Fall 2023. She is a PhD student in Computer Science and Engineering, and she is happy to work with other writers and help them improve their writing and communication skills.

0 Comments

“Looking at a blank page (or, more likely, a blank Google Doc) is daunting for anyone, and finding motivation to start and continue the writing process is a challenge,” states writing partner Katy Wolff. Almost all the writing partners at The HUB admit to this. For example, Lindsey Kendall adds, “I often find myself overwhelmed before starting to write for any big paper. Sometimes I have lots of ideas swirling around in my head but don’t know how to put them down on paper, and other times my mind simply draws a blank. In either situation, I find it difficult to start putting words on the page.” In this blog post, the HUB writing partners gather some tips that can help you overcome the challenge of getting started with writing or continuing the writing process.  Start early: First of all, CJ Oshiro emphasizes the importance of starting the writing task early. He explains, “Giving yourself time to work on a paper over a few days will allow you to mitigate challenges such as writer's block. You also write best when you're not stressed about a deadline.”  Break down the prompt: To understand the requirements of the writing task, several writing partners recommend breaking down the prompt. “Address what it is exactly saying and figure out what is expected of you. Then you can have a better idea of what you should be writing and can hopefully start curating ideas,” suggests Lady Elizabeth Roy. Kevin Shimizu adds, “First, you need to understand the goal of the paper (argue, explain, analyze, etc.) and to essentially understand what the prompt is specifically asking. You can do this by breaking down the prompt into separate ideas. From there, you can attack each idea separately, writing as much as you can remember about each one to get a baseline of where you are in understanding. If your understanding is not at the point where you can write anything about the individual parts, then go over the text, strengthen your understanding, and reapproach these steps. Once this is laid out, you can look at the goal again, and with each idea, put them together like a puzzle.”  Create an outline: After understanding the prompt, some steps can help you before starting the actual writing process. One of these steps is to create an outline. For example, Lucia Heese recommends outlining ideas and how they connect to each other. Lady Elizabeth Roy adds, “Create an outline of what you want to say. What are the most important topics that you want to touch on? How do you connect to this writing to maintain your voice?” Furthermore, Seta Salkhi explains, “If seeing a skeleton draft will help you build up your ideas, then start with an outline! Make sure you incorporate your assignment criteria and relevant quotes or ideas that fit into each requirement. From there, you can continue expanding on your ideas. Sometimes, though, it’s easier to just put words to the page. Start from wherever you feel you have the most content and keep going from there.”  Prewrite: Other writing partners emphasize the importance of the prewriting stage, which also precedes the actual writing stage. “The prewriting stage is when you brainstorm ideas, collect your information, and write them down in a document. It will make starting your actual writing easy because in this case you are not starting from scratch,” explains Maha Issa. Additionally, Jordan Scott encourages you to begin thinking about the prompt as soon as possible instead of waiting for the right time that fits into your schedule. She also lists many questions to think about in the prewriting stage. “What immediately comes to mind when you think of the prompt? What would be easy to write about? What is your honest perception? Do you have any questions about what the prompt is asking from you, implicitly or implicitly? Address and think through all these ideas before you even begin sitting down to write. Reference source material and think about the context of the class as you begin the process, and never begin writing before you outline,” she elaborates. It can also help to think about your own ideas and goals when you’re beginning to write. For example, Madeline Coquilla emphasizes how important it is to consider “What YOU want to write.” She states that sometimes it can be good to “go over the rubric later” so you can focus first on your own ideas for the text. Another task to complete during the prewriting stage is to look at other people’s works, as suggested by Lady Elizabeth Roy. She states, “Look at previous works and see if they can give you inspiration. Other works can help you with your own ideas.”  Just start: Once you created an outline and completed all your prewriting tasks, you are ready to start. Lady Elizabeth Roy recommends using a timer for 30 minutes to force yourself to write whatever flows from your mind. She adds, “Just putting yourself in the mindset to get writing can make all the difference.” If you don’t know where to start, here are some additional tips. Lucia Heese suggests, “Even if you have no idea what to write about a topic - even just writing I don’t know what to write about ________ can get the brain triggered to keep going.” Lindsey Kendall adds, “Frequently, if I feel too overwhelmed to start drafting, I will go through the texts and pick out some of the quotations that support the ideas that I want to talk about. From that, I can build analyses of those quotes to help me begin to get in the flow and think about the topics. Then, I try to sort of work backwards to formulate body paragraphs. Usually by this point I begin to get in the right headspace and the writing starts to flow much easier. It took me a long time to realize that you don’t have to write in order.” Additionally, Katy Wolff states, “A lot of the time, I find myself struggling with being willing to put down ideas that aren’t going to end up being my final words or arguments, but pushing yourself to just start writing down whatever you have in your head can really help you get over any mental blocks you might be having and allow your thoughts to start flowing more freely. Even if the words start out as almost incoherent thoughts (like mine often do!), if you keep going, you’ll often find that the incoherence starts to morph into material that you can actually use, whether it’s rough drafts of paragraphs, lists of ideas or points you want to make, or anything in between. Having this as a basis will allow you to continue your writing process and come back to your document later to refine and synthesize the results of your brainstorming.” Finally, if you want to experiment with some different options, consider what Lucia Heese suggests: “Sometimes I’ll write by hand if I’m feeling pressed for time because it forces me to slow down and make sure my ideas come out on the page (Retyping up your handwritten work can act as another form of revision).”  Take a break: Writing tasks often cannot be completed in one sitting, especially if you are writing a long piece. Several writing partners admit to this and recommend taking breaks in between. The reason behind such a recommendation is explained by CJ Oshiro: “In psychology, there is a phenomenon called the Einstellung effect which explains that you become fixated on one approach to the given task. Taking a break helps your mind free itself from one mode of thinking and explore new avenues to solve the problem.” Lady Elizabeth Roy adds, “Take a break and then come back to the writing, this can help you have a new set of eyes. When you come back you don’t always have to write in chronological order, you can start at any point (the ending, intro, conclusion) — just know that this means you’ll have to go back through the paper and reread your ideas in a cohesive fashion. Feel free to move paragraphs around (copy and paste is your friend).”  Discuss your ideas with others and visit the HUB: During any stage of your writing process, discussing your ideas with others would be helpful for you. Maddie Vitanza explains, “When I find myself drawing up a blank, unable to write any further, I find it helpful to briefly step away from my work and go back to basics. One of my favorite strategies here is to walk through my ideas aloud with a partner or group. This could be a housemate, a professor, a fellow peer—anyone. Though it may sound silly, this tactic allows the writer to achieve a deeper understanding of what they want to say; and how they want to proceed. Your partner or set of partners can bounce around ideas and perhaps offer guidance, acting as a useful sounding board for your thoughts.” And of course, discussing your thoughts with a writing partner is always a good idea. “If you feel unsure as to who might participate in this activity, feel free to make a visit to the HUB! We are always open for a brainstorming session to flush out your ideas—talking is often a more useful tool than you might think”, adds Maddie Vitanza. Lady Elizabeth Roy adds, “Meet with a HUB writing partner to help continue the writing process or get you started. It can even be helpful to meet with a writing partner and simply write in silence, asking questions along the way if you need to (this can be viewed as an accountability partner).” About the AuthorMaha Issa has been a graduate writing partner at the HUB writing center since Fall 2023. She is a PhD student in Computer Science and Engineering, and she is happy to work with other writers and help them improve their writing and communication skills. Hello Honors students! If you are reading this blog post WE (Lady Elizabeth and Natalia) can only assume you’re a junior or senior working on your senior thesis project. Good luck! No, it's all jokes, we bet you’ll do just fine. 😁👍 Trust us, the process is hard but totally doable. We are Senior Honors students currently going through the process and figured why not create a helpful “how to” post for all the arts and science peeps. But who knows, these tips might also help engineering and business students! Before getting into the tips, here are some things Natalia and I wish we had known before starting our project:

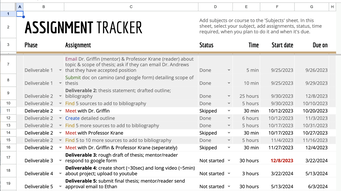

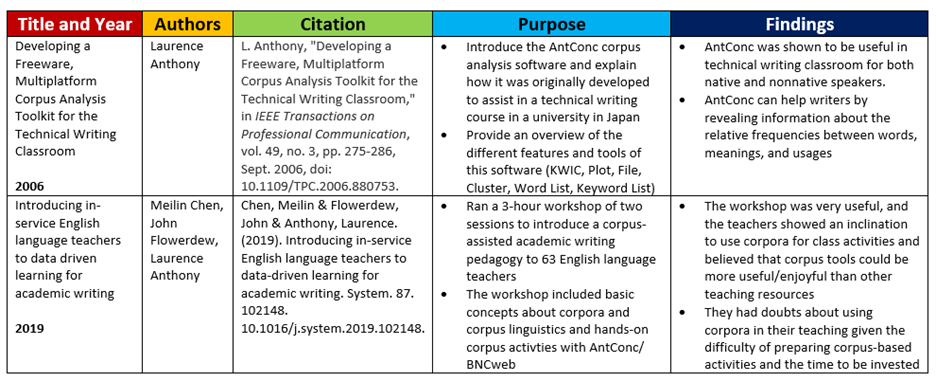

That’s right, this project is a handful requiring not only discipline but great guidance. Without further ado let’s learn from our experience. Tip 1: Start figuring out your thesis focus and mentor/reader sooner than later The order of which comes first doesn’t matter. You just need to pick a thesis focus and reader/mentor by the end of Spring Junior year. For readers, you can choose any professor you would feel comfortable meeting with for writing advice. When it comes to picking a mentor, it’s a little trickier. It’s best to pick a mentor in the field most related to your area of interest. Your mentor doesn’t have to be an explicit professor of your narrowed down topic but they should have enough background knowledge on the general focus to help you get started. For example, I (Lady Elizabeth) knew I wanted to focus my honors senior thesis on the American prison system, so I intentionally picked a mentor whose curriculum focused on mass incarceration. That way, my mentor would be able to suggest credible sources, books, and documentaries for me to look into as I narrowed down my topic. Meanwhile, I (Natalia) have been working on a research project with mentors from the English department I had chosen previously. Because of my busy senior-year schedule, I decided to use this project for my Honors Thesis. If you also have another project you are completing throughout the year in your respective program, I suggest checking to see if it could count as your Honors Thesis. This way you might already have your mentor picked out and just need to figure out a reader!  Tip 2: Pick a topic that you’re interested in Your topic does not have to be related to your major – this could be the chance for you to explore an interest in a different discipline or something that has been of interest to you. But please pick a focus that interests you, whether it’s major-related or not because this is a 9-month journey. That is why, despite being a psychology major, I (Lady Elizabeth) chose a topic aligned with sociology and ethnic studies, it was more interesting to me. While, I (Natalia) chose a topic related to my English major, and was an area of interest I did not get to fully explore during my undergraduate classes.  Tip 3: Schedule multiple meetings with your mentor & reader Please keep in contact with your mentor, as they are a resource to help guide you through your project. Having multiple sessions with your mentor and reader can ensure you stay on track. You can also get more guidance on how you wish to structure your paper (if that’s something you want). Plus this builds a good rapport between your mentor/reader and yourself. I (Natalia) met with my mentor almost weekly to help keep myself accountable and on track. This is a great way to ensure that your project does not feel like too much work at the end of your senior year! Tip 4: Create a timeline – this will be your lifeline This is crucial as the project is more than likely independent, so creating a timeline can be another way of holding yourself accountable. You can use the Google Sheets template (here) to help you set deadlines. Google Calendar is also a great way to help set deadlines. The Assignment Tracker image is a snapshot of my (Lady Elizabeth) mode of tracking my progress. It was helpful for me to write out when everything needed to be done and mark it off as I went. Whereas for me (Natalia) it was helpful to use Google Calendar and set aside time to work on my project. Tip 5: Visit the HUB! Coming to the HUB can be helpful at any point in your thesis. During the brainstorming stage, speaking with a writing partner can help you talk your ideas out loud, create a plan for the road ahead, gain inspiration, make ideas more specific, etc. Once you have a draft (partial or full) a writing partner can provide feedback regarding editing, analysis, grammar, structure/organization, etc. The HUB is a resource that can provide you with any kind of writing help you may need! As of Spring 2024, the HUB Writing Center has 10 writing partners in the Honors program: Faith Fitzpatrick, Jordan Scott, Katy Wolff, Lady Elizabeth Roy, Lindsey Kendall, Lucia Heese, Maddie Vitanza, Natalia Cantu, Rhiannon Briggs, and Thomas Matthew. Even I (Lady Elizabeth), a HUB writing partner, still find myself coming to the HUB occasionally, because it is a great resource. For the Honors Senior Thesis project, I met with Natalia (the other author of this blog post) to help me further work out the mental blocks I experienced while working on this paper. We hope that this was helpful as you progress on your SCU Honors journey. Happy writing! About the AuthorsLady Elizabeth and Natalia are seniors at Santa Clara University. Lady Elizabeth is a psychology major who has been working at the HUB since Fall 2021. Natalia, an English major with a minor in biology, has been working at the HUB since Fall 2022. Whether you are a PhD or master’s student, or even an undergraduate student conducting research, you are most likely going to write research articles. Although this task might seem difficult, dividing your writing process into stages will make it easier for you. This blog post will help you recognize how to write Engineering research papers and to understand the steps involved in the three different stages of writing: prewriting, writing, and rewriting. The prewriting stage: The prewriting stage constitutes the biggest proportion of the writing process. It involves:

The writing stage: Once you create the visuals that you want to include in your paper, you can now move to the actual writing stage. In contrast with the previous stage, this stage usually constitutes the smallest proportion of your writing process. A typical engineering research article includes the following sections: abstract, introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, and references. However, writing your sections in the same order as they appear might be inefficient. Here is the recommended order for writing your sections in addition to the content of each one:

The rewriting stage: Once you are satisfied with the content of your first draft, you can move on to the next stage: the rewriting stage. This is where you revise, edit, and proofread your draft to make it clearer, more appealing, and free of errors. Here are a few tips to consider in this stage:

Finally, keep in mind to always check the guidelines of every journal or conference to which you are submitting your article. Some of them may require you to follow a specific format that is slightly different from the one discussed above. For example, some may require you to add a new section, while others may require you to combine some sections, such as the introduction and literature review sections, or the results and discussion sections, or the discussion and conclusion sections. Additionally, check their page or word limit and plan accordingly. And most importantly, remember to visit The HUB Writing Center to get some writing feedback and suggestions to improve your draft before you submit! Applying for graduate school could be a very stressful period, especially with the large number of different essays that are typically required. However, if you understand the process and work step by step on every part of your application, you may be able to secure your spot in your program of interest. One of the essays required in almost every graduate school application is the Statement of Purpose (SOP). As its name suggests, this essay should focus on your future intentions. It should clearly communicate your goals, explain how and why pursuing a graduate degree would help you achieve these goals, and convince the admission committee that you are a good candidate. This blog post will help you understand the major components to include in the SOP, give you ideas on how to organize it, and provide you with some stylistic and grammatical tips to make your SOP stand out. Planning and brainstorming: The first step in writing your SOP is brainstorming the ideas that you want to include. This step should typically start two to three months prior to the application deadline in order to have enough time to gather the appropriate information. To begin, start thinking about your experiences and accomplishments. Usually, such experiences should preferably be research oriented, especially for PhD applications. Ask yourself questions like: What are the research projects that I have worked on? What did I learn during my work? What was my own contribution to these projects? What was the outcome of these projects? For example, did they get published? Did they provide an important advancement to my research field? Additionally, you may think about including information regarding other experiences, such as work or teaching experience; however, only include these if they are relevant to the program to which you are applying. If they are irrelevant, they are probably not going to help you convince the admission committee that you are a good fit for their program. Use your limited space wisely to elaborate on the components that are more related to your area of interest. Then, carefully look at the website of the university to which you are applying in order to find potential professors with whom you would like to work. For each professor in your intended department, check their personal website to familiarize yourself with their research interests and accomplishments. This will help you identify several professors whose research interests align well with your own interests and experiences. This is very important because if you are applying to a program where none of the professors conduct research in your area of interest, your chances of being accepted will probably be low. The university website is usually the most helpful and accessible way to get familiar with faculty members and their research areas; however, there are of course many other approaches, such as connecting with them through LinkedIn or email, or even reaching out to current graduate students in the same department. In addition to identifying potential professors of interest, you could also identify any resources at the university that might help you achieve your main goal. Writing your first draft: Once you have gathered your ideas, you can start drafting your SOP. To get an idea on how to organize your essay, you can examine some SOP samples in your field of study, either by searching for online resources or asking some colleagues who were already accepted into graduate school. Looking at how other people in your area organize their SOPs will help you understand the conventions of your field and recognize the expectations of the admission committee. A typical organization of the SOP could be as follows:

Revising, editing, and proofreading: Once you are happy with the content of your first draft, you can start revising your document to make any necessary edits, improve its readability, and correct any grammatical mistakes. Here are some of the most important aspects to consider when revising your SOP:

Some pitfalls to avoid: Throughout the writing process, remember to:

Finally, always check the given SOP prompt before starting to draft your essay because it might be different from one university to another, and even from one department to another. Also, consider customizing your SOP for every university and program to which you are applying. And most importantly, remember to ask your friends, colleagues, professors, and the HUB writing partners to read your SOP and give you their feedback! About the Author: Maha Issa is a graduate writing partner at the HUB writing center since Fall 2023. She is a PhD student in Computer Science and Engineering, and she is happy to work with other writers and help them improve their writing and communication skills. Wondering what to do with four weeks of free time this Winter Break? Try picking up one of these awesome reads, curated by your favorite Writing Partners! Keep scrolling to read our collection of one-sentence book recs!  The Club by Ellery Lloyd "This book is a murder mystery that has a great build up and comes with various twists and turns!" -Faith Fitzpatrick  The Secret History by Donna Tartt "Set against a backdrop of cold weather and dark academia, this captivating and suspenseful story follows college students studying Greek." -Jordan Scott  Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann "It was a great read that was incredibly eye-opening to the horrible injustices that happened so recently in our modern history. " -Jessica Garofalo  The Color Purple by Alice Walker "The color purple made me reflect deeply about my faith." -Jonathan Terryn  My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh "Nothing really happens in this book... yet I was left feeling deeply disturbed in the end." -Nadine Koochou  The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides "Whatever you think you know, you don't. Trust me, you won't know whodunit until Michaelides tells you." -Seta Salkhi  Normal People by Sally Rooney "Sally Rooney puts into words the nuances of interpersonal relationships and the human experience in a beautiful way." -Lindsey Kendall  Dear Justyce by Nic Stone "Dear Justyce is a the sequel to Dear Martin, refrencing the stark realities and issues within the juvenile justice system." -Lady Elizabeth Roy  Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese "Verghese transports you to the beautiful state of Kerala in his story about a family plagued by a mysterious medical condition." -Mathew Thomas  A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki "It changed the way that I think about the world." -Nicole Bloch  Luster by Raven Leilani "It's a beautiful and really engaging character study of a young Black woman as she navigates personal struggles, including a complex relationship with an older white man who is in an open relationship with his wife." -Katy Wolff  Lord of the Butterflies by Andrea Gibson "A beautiful collection of queer poetry that really helped ground me when I was feeling listless." -Madeline Coquilla  Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH by Robert C. O'Brien "A great novel about knowledge as power and ultimately a sort of commentary on animal testing, as well." -Maddie Vitanza  Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata "It's a unique, funny, and sometimes sad novel centered around a woman who works in a convenience store." -Natalia Cantu  A Study In Scarlet by Arthur Conan Doyle "This book is British, the first Sherlock Holmes novel, and has plenty of cool words to learn." -John Paul Kraus  We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom "The stunning artwork and narrative present an academically informed children's story on the indigenous movements of the Water Protectors - a good read for children and adults." -Lucia Heese  Les Misérables by Victor Hugo "It's remarkably well written, and despite being emotionally challenging, it's satisfying to watch the characters grow and come across good fortune." -Jwwad Javed  A River Enchanted by Rebecca Ross "If you're in the mood for a magical and lyrical fantasy story, this is for you!" -Anj Zanger  A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway "This memoir is written in beautiful prose and is sure to inspire any writer." -Rhiannon Briggs About the Author

Nadine Koochou is a Senior studying English with minors in Creative Writing and Women's & Gender Studies. When she's not reading and writing, she enjoys baking treats, spending time outside, and practicing yoga. “You once told me that the human eye is god's loneliest creation. How so much of the world passes through the pupil and still it holds nothing. The eye, alone in its socket, doesn't even know there's another one, just like it, an inch away, just as hungry, as empty.” -Ocean Vuong, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous

I have a fatal flaw. Whenever someone recommends something to me—be it a TV show, a movie, or a book—it’s like I am suddenly incapable of viewing it. It’s strange because I am constantly searching for some new piece of media to satisfy the itch in my brain, yet when someone provides something to scratch it, I become avoidant. I’m sure there’s some psychology to this, but I am going to be literary for a moment. Sometimes I feel that, with books in particular, there’s some small part of me that is scared of finding just the right one. Like, if I read a book that someone tells me I’m sure to like, and I end up loving it, I might never find a book so perfect again. Such is the fear I felt when I picked up On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong. Written as a letter to his mother who cannot read, the narrator in Vuong’s novel paints a breathtaking portrait of his life, centering around his relationship with his mother. When the narrator (who remains unnamed throughout the novel, only referred to as “Little Dog”) was a baby, his mother and grandmother immigrated from Vietnam to the United States. Over the course of the novel, we learn about the family’s generational trauma connected to the Vietnam War, their difficult transition to life in the States, the strained relationship between mother and son, and the confusion and shame the narrator experiences as he explores his sexuality with another boy. This book is autofictional, meaning that Vuong blends aspects of his own life (autobiography) with a fictional story. In this way, Vuong crafts a hauntingly vulnerable story that reflects on the realities of abuse, war, immigration, poverty, and more. Now, why did I feel that this book would destroy all books for me? I had previously read Vuong’s collection of poetry, Night Sky With Exit Wounds, and I found myself reflected in his subject matter. So, going into his novel, I knew that Vuong would leave no stone unturned—and I was right. Not only does Vuong create a story which is refreshingly aware of the complexities of being human, but he does so using unabashedly poetic techniques. Vuong is a poet first, and this is evident from the first page of the novel; I often needed to pause just to let the words wash over me once more. Also, I cried. A lot. Which, if you know me, you know I love a book that makes me cry. The simple knowledge that, in all his vulnerability, the narrator’s mother cannot possibly read his letter brings me to tears. And that is the power of Ocean Vuong’s novel. So, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is easily one of the best books I’ve ever read. But, rather than ruining all other books for me, Vuong’s novel left me with a longing to search for more such stories. His novel introduced me to a style of writing and a subject that there is just not enough of in mainstream literature, making his work all the more essential. Ultimately, I was right to listen to the people who recommended On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, so here I’m asking you to do the same. Read this book, and I promise you won’t regret it. About the Author Nadine Koochou is a Senior studying English with minors in Creative Writing and Women's & Gender Studies. When she's not reading and writing, she enjoys baking treats, spending time outside, and practicing yoga. NPR recently reported that Ethan Mollick, a business professor at the University of Pennsylvania, claimed that “AI has basically ruined homework" (Bowman). To see if this theory holds, I prompted the AI service called “Chat GPT” with the following prompt: write a 500 word paper about the themes and poetic techniques in "the lady of shalott" It spent around 10 seconds “thinking,” and then typed out the following text: "The Lady of Shalott" is a poem by the English poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, first published in 1832. The poem tells the story of a cursed woman who is forced to live in a tower on an island in the middle of a river. She is only allowed to look at the world outside of her tower through a mirror, and must weave a tapestry of what she sees. However, if she ever looks directly at the outside world, she will die. One of the main themes in the poem is the idea of confinement and isolation. The Lady of Shalott is physically confined to her tower, unable to leave or interact with the outside world. This isolation is further emphasized by the fact that she is cursed and cannot look directly at the world outside. This theme is symbolized by the tower itself, which serves as a prison for the Lady of Shalott. Another theme in the poem is the idea of art as a form of self-expression. The Lady of Shalott uses her tapestry as a way to express her feelings about the world outside of her tower. Her tapestry is a reflection of her inner thoughts and emotions, and serves as a way for her to connect with the outside world. This theme is symbolized by the tapestry itself, which serves as a window into the Lady of Shalott's mind. A third theme in the poem is the idea of the destructive power of love. The Lady of Shalott becomes infatuated with Sir Lancelot, a knight who passes by her tower every day. She cannot resist the temptation to look directly at him, despite knowing that it will mean her death. This theme is symbolized by Sir Lancelot himself, who serves as a reminder of the destructive power of love. The poem also makes use of several poetic techniques to convey its themes. One such technique is imagery, which is used to create vivid and detailed descriptions of the setting, characters, and events in the poem. For example, the imagery of the tower and the tapestry serve to emphasize the themes of confinement and art as self-expression. Another technique used in the poem is symbolism, which is used to give deeper meaning to the characters and events in the poem. For example, the tower and tapestry are symbols of the Lady of Shalott's confinement and her art, respectively. Sir Lancelot is a symbol of the destructive power of love. The poem also makes use of personification, which is used to give human qualities to non-human objects. For example, the mirror is personified as "the silent isle" which "awoke and cried, the curse is come upon me!" Finally, the poem also uses repetition, which is used to create a sense of inevitability and to emphasize important themes and ideas. For example, the phrase "the curse is come upon me" is repeated multiple times throughout the poem, creating a sense of inevitability and emphasizing the theme of the destructive power of love. In conclusion, "The Lady of Shalott" is a poem that explores several themes, including confinement and isolation, art as self-expression, and the destructive power of love. The poem makes use of several poetic techniques, including imagery, symbolism, personification, and repetition, to convey these themes and create a vivid and powerful reading experience (“Chat GPT”). I’ve spent a few hours messing around with Chat GPT, testing its knowledge on academic subjects (primarily in the fields of my majors, English and Economics). I genuinely liked the idea of college students mischievously smiling at their computer as they watch the bot whip out line after line of their long-despised English assignment, sending teachers around the country into panic. However, from what I can see of Chat GPT’s essay-writing skills, I have come to the same conclusion that I hope most college students (and teachers) would: it’s not good. In other words, given a prompt, Chat GTP cannot produce a well-crafted stylistic essay that adroitly answers the prompt. While there are serious limitations to Chat GPT’s writing abilities in its current form, it does not lack its fair share of surface-level advantages, the most obvious one being the minute amount of time it takes to generate a stream of focused paragraphs, coherent sentences, and reasonable summary around any prompted topic. The above essay, produced by Chat GPT, analyzes “The Lady of Shalott,” a poem by Alfred Tennyson, who was a 19th century Poet Laureate of the UK. After reading this essay, I conclude that Chat GPT is a terrible resource for producing academic essays (or brainstorming for them) due to its limitations in (writing) style, analysis, and credibility. Close reading, on the other hand, has been proven to be an effective tool for students writing essays due to its advantages in numerous areas such as specific analysis and commentary on the sound[1] of a poem. Chat GPT clearly struggles with mimicking human writing styles, which it shows through its remarkably high redundancy. For each of the three themes it identified, the AI repeats a phrase of the form “the theme is symbolized by [blank] itself, which serves as a…” every single time (“Chat GPT”). The same problem recurs when it addresses the poetic techniques—it follows the exact same structure for each one it introduces. Specifically, it repeats the phrase, “which is used to …” followed by an atrociously generalized description of the technique (“Chat GPT”). The repetition is so pervasive and unintuitive that it would clearly be looked down upon by any sophisticated human audience (and this is rather ironic because repetition is one of the things that Chat GPT attempts to analyze in “The Lady of Shalott”). If a student tried to turn this essay in as their own work, the conspicuous repetition would certainly raise the teacher’s suspicions about the essay’s authenticity and probably induce a conniption of cringing as well. Therefore, Chat GPT completely fails to produce a satisfactory essay that even remotely resembles a respectable human writing style. In the realm of analysis, Chat GPT offers next to none. It often makes a claim, provides an example, and moves on to the next paragraph. For instance, it ends the sixth paragraph with the claim that “Sir Lancelot is a symbol of the destructive power of love” (“Chat GPT”). Although this claim is feasible, there is no explanation or significance to substantiate it. Since this is the last statement of the paragraph, the AI leaves the reader wondering about Sir Lancelot’s significance in the poem and how exactly he symbolizes the destructive power of love. Another example of absent analysis is in the third-to-last paragraph of the essay, where it mentions that the poem “makes use of personification,” provides an (incorrect) example (it claims the mirror cried “the curse is come upon me” when this was clearly said by the Lady of Shalott), and goes no further than that (“Chat GPT”). Even if this was a real case of personification, I would be interested in knowing what role personification played in the development of a theme, why the author decided to include it, or what effect it might have on a reader. Chat GPT completely disregards all of these concerns by simply moving on to the next paragraph. In contrast, a close reader would explain the evidence, show the significance of it, and in doing so, enhance their essay’s argument. If I were to perform a close reading analysis on “The Lady of Shalott,” here’s how I might go about it: I would address the rhyme scheme by distinguishing where the poem sounds pleasant or predictable and where it doesn’t. For example, in the last stanza of the poem, I would note the ending words of three of the lines: “curiously, utterly, this is I” (Lord Tennyson). Tennyson surprises the reader here because he deliberately and drastically defies the rhyme scheme he established up to this point: “curiously,” “utterly,” and “this is I,” do not rhyme with each other while “dame,” “came,” and “name”—the words in the exact same position (in the previous stanza)—do (Lord Tennyson). Similarly, almost all other stanzas have three rhyming words ending the lines in this position. However, in the last stanza, Tennyson completely breaks the rhyming pattern to create a sense of discomfort in the reader. This discomfort accompanies the sinister picture of people finding a cadaver floating into their castle. The rhyming dissonance could mean many things, but Tennyson may have intended to show people that it’s uncomfortable to challenge society’s expectations (particularly those around women’s sexuality) or that it’s unpleasant to watch women fall prey to these expectations in reality. As this close reading analysis shows, students must use their human experiences to interpret a poem. A well-written essay speaks to the sound, feelings, and awareness that a poem evokes. Chat GPT has yet to display a recognition of these dimensions (especially rhyme scheme) and has thus revealed another area where the AI’s writing abilities fall considerably short. Perhaps the most major concern about Chat GPT revolves around its inability to provide reliable information. For example, in the fourth paragraph, it claims that Lancelot “passes by her tower every day” (“Chat GPT”) when that is not the case—in the poem, he is simply described as riding down from Camelot once with no hint that he has ridden there before (Lord Tennyson). Also, in Chat GPT’s penultimate paragraph, it comes up with an incorrect example of repetition. It claims that the phrase, “the curse is come upon me” is “repeated multiple times throughout the poem” (“Chat GPT”), which is simply false. When attempting to identify repetition, not only did the AI come up with a blatantly wrong statement, but it also missed the obvious repetition of the phrase “the Lady of Shalott.” Only someone who has not fully understood the poem might believe the first fallacy (the one about Lancelot passing by daily), but anyone who takes a glimpse at the poem would catch second one. These examples reveal the serious limitation of Chat GPT: everything it produces needs to be verified—some errors are obvious, and others are quite subtle. In order to accurately check all of Chat GPT’s statements, students must employ close reading techniques. While Chat GPT certainly has its flaws, the first paragraph of its essay shows that it can provide a decent account of what happened in the story—as long as the reader takes the specific details with some degree of skepticism. Also, the structure of the essay is passable. After starting with a summary of the poem, it sets up body paragraphs to answer the prompt. It uses correct grammar and sometimes even stumbles upon a correct technique the author uses. For example, it identifies a time where Tennyson used symbolism: it claims that the tower is a symbol of the Lady of Shalott’s confinement (“Chat GPT”). Here, the Chat GPT essay lacks the necessary context and analysis to establish the symbolism and ascertain its meaning, but something like this would be a good starting point for a student to expand on in their own essay. For example, one could claim that the tower confines the Lady of Shalott in the same way that society confines women; therefore, the tower symbolizes society. This interpretation, however, is quite far from the original claim that Chat GPT came up with, and takes a fair share of close reading (for one to understand both what happens in the poem and the historical context around it) to create. I disagree with Professor Mollick—chat GPT has certainly not ruined homework, at least not in poetry analysis. As its insufficient essay about “The Lady of Shalott” has shown, Chat GPT is far from a panacea, and not just because of its redundancy. AI clearly cannot obviate our need for close reading—its consistent lack of analysis and credibility force students to perform the close reading analysis anyway. Ultimately, in its current form, Chat GPT is largely a waste of time in regard to essay generation, and close reading remains the inevitable way to get that stupid essay done. [1] The elements of a poem that impact the way the poem is spoken or heard by a human. For example, the rhyme scheme and meter affect the “sound” of a poem. Works Cited: Bowman, Emma. “A New AI Chatbot Might Do Your Homework for You. but It's Still Not an A+ Student.” NPR, NPR, 19 Dec. 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/12/19/1143912956/chatgpt-ai-chatbot-homework-academia. “ChatGPT.” Chat.apps.openai.com, https://chat.apps.openai.com/. Lord Tennyson, Alfred. “The Lady of Shalott.” Poetry Foundation. 2023, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45359/the-lady-of-shalott-1832 About the Author: John Paul Kraus is a Junior English and Economics major at Santa Clara University. He is particularly interested in AI and it's role in academia as a tool for enhancing learning.  Broncos we have officially made it past the halfway mark of the Winter quarter! Whether you have already completed all of your midterms or you have more to come, have you considered visiting the HUB for any writing assignments? At The HUB, writing partners are here to support you with any piece of writing no matter what stage of the process you are in. The HUB is a resource available to all SCU writers, but some people may be hesitant about scheduling a session not knowing what to expect during an appointment. So I am here to address some of that uncertainty by explaining what a typical session may look like. Writing partners are here to help you in any way you need, so a session will look different for each writer and each assignment but here are a few things you can expect. To begin, we offer in-person, online synchronous, and asynchronous sessions; while these appointments may look different in practice they all operate under the same principle: we want to help writers develop as writers. Therefore HUB sessions will stray away from direct line editing in favor of a fulfilling learning experience for the writer. Here are some techniques you might expect in a session!  Questions: HUB sessions often thrive on questions. Since it is our goal to help you grow as a writer we will answer any questions you may have and will ask you questions about your content and processes. These open-ended questions are designed to help you think through your writing and develop skills for future writing. Proofreading Techniques: Writing Partners will often encourage you to read sections of your work out loud or read it out loud themselves. Doing this often helps writers notice little flow or phrasing issues. This is entirely dependent on your comfort level; a writing partner will never make you do something you are not comfortable with or that you think won’t add to your learning experience!  Reflection: Some writing partners will encourage you to reflect on your own writing and your main concerns. This is intended to help you recognize why you feel concerned about certain aspects of your writing or to notice what you are doing well. Praise: In nearly every session, writing partners will praise well-crafted aspects of your writing. Writing is hard work, and we recognize that, so writing partners will be sure to praise your stellar writing. Although these are typical techniques of HUB sessions, we are here to help you. Whether you just need another pair of eyes on your writing before you turn it in or need support in creating an outline, writing partners will be able to facilitate a meaningful experience centered around your writing. Schedule an appointment with a Writing Partner Sundays through Thursdays between 4 PM and 10 PM. About the Author: Anne Johnson is a senior writing partner who began working at the HUB in Fall 2022. She is an English major who loves all things about writing and wants to help you find enjoyment in it too. She is also involved with the campus newspaper The Santa Clara, as a news writer. Hello beautiful SCU writers!!! It’s week 5 of Winter quarter, and as we’re getting into the thick of it I have a friendly reminder for you: the HUB Writing Center is a resource for YOU!

The HUB has skilled writers who are ready to help with various writing assignments, including those pesky CORE requirements you may not have finished. Writing partners are also ready and able to help you figure out how to format your resumes, job applications, grad school applications, research papers, critical thinking essays, etc.

Come check out the HUB Writing Center anytime Sunday to Thursday from 4pm to 10pm. We’re located in the lower level of the SCU library, near the computer stations. We take walk-ins and scheduled appointments (although, I recommend scheduling ahead of time so you’re guaranteed a session). Don’t believe me? Schedule an appointment here today and find out just how helpful the writing partners can be! About the author: Lady Elizabeth, a junior at SCU who majors in psychology, has worked at the Writing Center since fall 2021. She is passionate about learning and helping others, whether it be with writing or in any other area. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed